“Who really knows?

Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?”

Rig Veda, 10:129-6

Somewhere embedded deep inside the Rig Veda — which happens to be one of the important canonical texts of Hindu religion, the four Vedas — is Nasadiya Sukta, or what is known as the hymn of creation. Of unknown authorship, this hymn poses some very cryptic and incisive queries on the purpose of life and the very existence of an all-bearing god. There is an element of agnosticism, of query, of doubt. It starts in a rhetorical fashion, posing incisive queries questioning the singularity itself. And while numerous interpretations of the Sukta have highlighted the scientific temper and the inquisitive  temperament of the early sages who penned this and the very many hymns found elsewhere, the fact remains that Nasadiya Sukta is also a very humane and emotional query. For instance, when asked to believe in something, don’t we always begin with scepticism and doubt, it is only later when through understanding and acceptance that we move to the next level. Until then, we are atheists, sceptics, agnostics and so on.

temperament of the early sages who penned this and the very many hymns found elsewhere, the fact remains that Nasadiya Sukta is also a very humane and emotional query. For instance, when asked to believe in something, don’t we always begin with scepticism and doubt, it is only later when through understanding and acceptance that we move to the next level. Until then, we are atheists, sceptics, agnostics and so on.

In that way Nasadiya Sukta is most special, it accepts doubt and empiricism as part of the man’s spiritual and scientific journey. It encourages questioning the very fundamentals, even the existence of a supreme being or many is not taken for granted. It is in this sense, Hinduism differed from all else, you did not have to believe anything that your rational mind did not. Faith was not a mandatory imposition; that is, not believing in the trinity — Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh — did not make you any lesser of a Hindu, than say a temple priest who spent a lifetime propriating the very triad. And so the ancient Vedic Hindu was a questioning, open-minded, person, not a self-deluded proud oaf who saw Meru as the centre of the universe, denying everything else.

Much has changed in the journey from a Vedic Hindu performing a homa on a vedi in the ancient time, to the modern Hindu blogging and posting on the Vedas on FB and Twitter today. The progress of technology and evolution has left its mark on the religion itself. New gods have emerged, old have been dislodged, there have been numerous reformist movements from Arya Samaj to Theosophical Society, from Iskcon to Art of Living. Hinduism probably is the only religion in the world, where new deities keep emerging at different time, and all the time. Take the case of Sai Baba, there are numerous temples dedicated to him and many more are sprouting all the time. In fact, Shirdi which was the seat of Sai Baba has become a huge pilgrimage centre, with annual donations running in many millions. Faith is always good business in any religion.

Sadly, the Vedas to a large extent have now been relegated to the domain of the experts and the scholars, with newer texts taking their place. The Hindu theology can be broadly classified into three buckets:

- Vedas & Brahmanas

- Upanishads

- Puranas & the Epics

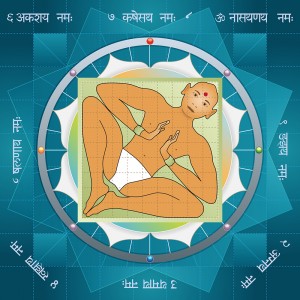

The four Vedas – Rig, Yajur, Attharva, Sama — primarily are a collation of hymns, rituals and prayers, propitiating the various Vedic deities (32 approximately), like Indra, Agni, Varun, Maruts, Prajapati. There’s much lesser storytelling in them, and whatever are there, the purpose is to present a reasoning for a certain ritual or sacrifice. For instance the tale of Apala in the Rig Veda provides a clue as to why certain rituals like the turmeric

ceremony is performed during the nuptials. Thus, the tales are a sort of story to explain the science. There is a purpose, a well-thought objective. The sheer depth and complexity of the Vedas are tempered by such tales. Also, it is important to note that there is a lot more cultural and scientific material in the Vedas, through careful examination and interpretation, one can understand the nature of being, and the natural world that surrounds it. Indeed, there is theology and philosophy, but only to a limited extent. For instance, we get to know about how the world was created through Purusha Sukta and to an extent the Nasadiya Sukta. Matters like philosophy of religion is dealt with much greater emphasis in the subsequent works like the Upanishads.

ceremony is performed during the nuptials. Thus, the tales are a sort of story to explain the science. There is a purpose, a well-thought objective. The sheer depth and complexity of the Vedas are tempered by such tales. Also, it is important to note that there is a lot more cultural and scientific material in the Vedas, through careful examination and interpretation, one can understand the nature of being, and the natural world that surrounds it. Indeed, there is theology and philosophy, but only to a limited extent. For instance, we get to know about how the world was created through Purusha Sukta and to an extent the Nasadiya Sukta. Matters like philosophy of religion is dealt with much greater emphasis in the subsequent works like the Upanishads.

So, broadly speaking Vedas are the scientific texts, Upanishads are the philosophical treatise, and by the time we reach the Puranas, all we are left with tales and myths. The Puranas are much later compositions and were written for a specific purpose to promote and endorse one deity over all else, thus in the Shiv Purana, you are told that Lord Shiva is ‘dev adi dev, mahadev’ (the super-duper god), the Vaishnav Purana would tell you about the Maha Vishnu, who creates a million universes with each breath lorded over by a smaller Vishnu in his own image. The Devi Purana, similarly pronounces the supreme-ness of the female deity. All this is done through prose stories, and almost every time the story of creation is reinvented with a new twist.

Meanwhile, the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana penned by Vyas and Valmiki respectively are Maha-Kavyas, great poems and work of fiction, like say Iliad and Odyssey. These are fantastical tales possibly of fantastical people and times, but then in lack of larger proof in terms of historical finding or artefact, they cannot really be considered as real.

Yet, since the epics are much a part of the religious ethos, the Hindus treat them  with much deference and respect. Considering that the two major Vishnu Avatars are at the core of each of this epic, raises the religious value of these works beyond comprehension. Little wonder, when the same epics were adopted on television the actors playing Rama and Krishna were treated like gods, and there are stories of how people would offer flowers and fruits to the TV when the episodes aired. In that particular timeslot the television set would turn into a temple of sorts. That is the power of belief.

with much deference and respect. Considering that the two major Vishnu Avatars are at the core of each of this epic, raises the religious value of these works beyond comprehension. Little wonder, when the same epics were adopted on television the actors playing Rama and Krishna were treated like gods, and there are stories of how people would offer flowers and fruits to the TV when the episodes aired. In that particular timeslot the television set would turn into a temple of sorts. That is the power of belief.

Little wonder, the amazing tales told in the epics, or even the Puranas, are not fiction for many. There are numerous who believe them to be real, and so many scholars and researchers spend their lifetime looking for clues, meanings and physical markings of all the things and places etched out in them. This is a sort of retrofitting research, wherein you try and find the physical manifestation of a fictional object or thing. People give real world dates, 4000 BCE, 8000 BCE, 80000 BCE and so on. Ramayana came first, Mahabharata second, and so on.

And this is essentially where the anomalies start, in the fascination and fastidiousness of proving the epics as historical contrivances, supposed scholars start building fancy hypotheses. Thus, a Brahmastra in Arjun’s quiver becomes an equivalent of an atomic missile, Ravan’s Pushpakvimana turns into an early age helicopter, Gandhari’s mechanism of having kids by raising 100 embryos in 100 earthen pots is like test-tube baby, replacement of Ganesha’s head with that of an elephant is surgical procedure, the Jambudweepa is another term of the ancient Pangea, the extreme slowness of Brahma’s time is actually time dilation, the Krishna’s precise and pinpointed Sudarshan Chakra is actually a cruise missile, and the list just goes on and on.

And this is essentially where the anomalies start, in the fascination and fastidiousness of proving the epics as historical contrivances, supposed scholars start building fancy hypotheses. Thus, a Brahmastra in Arjun’s quiver becomes an equivalent of an atomic missile, Ravan’s Pushpakvimana turns into an early age helicopter, Gandhari’s mechanism of having kids by raising 100 embryos in 100 earthen pots is like test-tube baby, replacement of Ganesha’s head with that of an elephant is surgical procedure, the Jambudweepa is another term of the ancient Pangea, the extreme slowness of Brahma’s time is actually time dilation, the Krishna’s precise and pinpointed Sudarshan Chakra is actually a cruise missile, and the list just goes on and on.

Looking from the prism of today, these scholars try to reinvent the past using the epics as the base. The core idea is to impress upon us that our lineage actually hails from a very scientific and advanced race. It is like reading Verne’s ‘20,000 Leagues under the sea’ and deducing that the medieval man had a powerful nuclear submarine like Nautilus, or using HG Wells novel to claim the indisputable existence of a time machine. The lines between fact and fiction gets blurred.

By the way, in no manner do I imply that our great ancestors were some pastoral oafs. Indeed they were ahead of their times, inquisitive and used science as a tool. Anyone who has ever visited any Indus Valley Civilization’s ruin — even excepting Harappa & Mohenjo Daro (because they are far too superlative to not impress) — would immediately realise the scientific temperament of the ancient Indians, the town planning, the right-angled streets, the sewer system, the trade mechanism, etc. do provide a glimpse into the scientific past. Continue reading