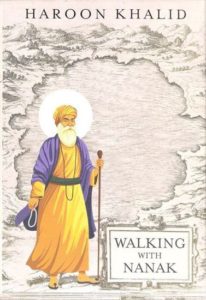

The first thing that immediately catches your attention is the beautifully illustrated cover, that has Guru Nanak in saffron robes, a staff in one hand and a rosary in other, all set for a long journey. And if the alluring illustration was not enough, the title itself invites you on a journey, Walking with Nanak, scores big in the first instance itself.

The author of this book is Haroon Khalid, who is a teacher by vocation and an avid traveler and writer by passion. This book is his third one, the other being A White Trail and In Search of Shiva. Basically, over the years Haroon has been writing on issues related to the minority communities in Pakistan, namely the Hindus and the Sikh. He is a sort of wandering chronicler who talks about the status and the current state of monuments related to Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan.

Search of Shiva. Basically, over the years Haroon has been writing on issues related to the minority communities in Pakistan, namely the Hindus and the Sikh. He is a sort of wandering chronicler who talks about the status and the current state of monuments related to Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan.

In the present book, Walking with Nanak, Haroon makes an interesting journey of all the important points of reference in Guru Nanak’s life as they exist in Pakistan. Guru Nanak was born in Rai Bhoi di Talwindi or what is known as Nankanasahib in 1469 and breathed his last in Kartarpur in 1539. In the 70 odd years that he lived on this planet, he made an astounding journey across the Indian subcontinent visiting places like Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia and so on. He apparently made 4-5 or five journeys that took him all over the place. Yet, at the end of it, he would return to his ancestral place in Pakistan at the culmination of each trip. Thus, because of this association with the first Sikh guru, the shrines in current day Pakistan are very important for the religion.

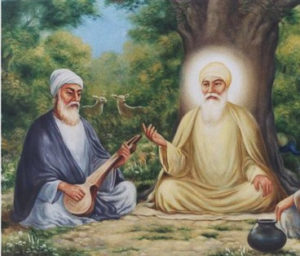

Guru Nanak traveled across all the places on foot and was accompanied by a companion  named Mardana, who was a Muslim man from his village. Mardana would accompany him and play rubab on which Guru Nanak would sing his poems. The bond between that of Guru Nanak and Mardana is that of a murshid (guide) and mureed (follower). Haroon too travels to all the sites accompanied by his murshid, Iqbal Qaiser, whom he considers to be his mentor (and much more). Being a scholar (self-taught) on Sikhism, conversations with Iqbal provide an interesting insight on what has been the religious state of affairs post partition.

named Mardana, who was a Muslim man from his village. Mardana would accompany him and play rubab on which Guru Nanak would sing his poems. The bond between that of Guru Nanak and Mardana is that of a murshid (guide) and mureed (follower). Haroon too travels to all the sites accompanied by his murshid, Iqbal Qaiser, whom he considers to be his mentor (and much more). Being a scholar (self-taught) on Sikhism, conversations with Iqbal provide an interesting insight on what has been the religious state of affairs post partition.

Relying on the Janamsakhis as a guide, Haroon “travels to historical places and witnessing the unfolding of history with imagination”. Through the pages we uncover the numerous legends pertaining to Guru Nanak’s life right from Sacha Sauda to Panja Sahib. We also encounter interesting legends like how Guru Nanak had cursed the village of Kanganpur with “May the village of Kanganpur prosper.” Meanwhile, he had blessed the village of Manakdele as,”this is a hospitable village and it was an honour to stay here. I hope that this village never prospers and remains small. May the villagers of Manakdeke scatter from this place to the different regions of the world.”

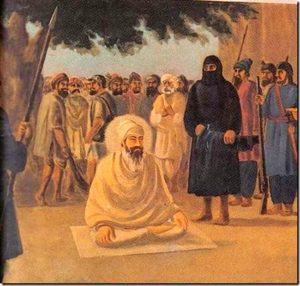

But Haroon does not limit himself to Nanak, he gives us an insightful overview of the Sikh history, giving us a ringside view of the intricacies of how the various Gurus rose to power.  And also tackling the contentious history of the relation between the Mughals and the Sikh Gurus. In a strange karmic way, the destiny of the Mughals seemed to be entwined with Sikh Gurus. For instance, the first Mughal king Babur had an encounter with Guru Nanak, whom he jailed for a few days in 1519. Post that in 1606, the 5th Guru Arjan Das was executed and Guru Hargobind was incarcerated on the orders of Emperor Jahangir. Then in 1675, the 9th Guru Tegbahadur was killed on the orders of Emperor Aurangzeb. And then in 1707, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb died, and the empire when into decline, the last living guru of the Sikhs, Guru Gobindsingh was murdered by Pathan horsemen in 1708. Haroon deals with this history at length, chronicling the transition of the Sikh Gurus as a religious head to that of a military one, like the formation of the Khalsa by Guru Tegh Bahadur. He also touches upon the fratricidal conflicts like the one with Prith Chand on the selection of his younger brother Arjan as the Guru. Or even the objection by Guru Nanak’s elder son and wife to the appointment of his disciple as a successor.

And also tackling the contentious history of the relation between the Mughals and the Sikh Gurus. In a strange karmic way, the destiny of the Mughals seemed to be entwined with Sikh Gurus. For instance, the first Mughal king Babur had an encounter with Guru Nanak, whom he jailed for a few days in 1519. Post that in 1606, the 5th Guru Arjan Das was executed and Guru Hargobind was incarcerated on the orders of Emperor Jahangir. Then in 1675, the 9th Guru Tegbahadur was killed on the orders of Emperor Aurangzeb. And then in 1707, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb died, and the empire when into decline, the last living guru of the Sikhs, Guru Gobindsingh was murdered by Pathan horsemen in 1708. Haroon deals with this history at length, chronicling the transition of the Sikh Gurus as a religious head to that of a military one, like the formation of the Khalsa by Guru Tegh Bahadur. He also touches upon the fratricidal conflicts like the one with Prith Chand on the selection of his younger brother Arjan as the Guru. Or even the objection by Guru Nanak’s elder son and wife to the appointment of his disciple as a successor.

But this book is not merely a historical account or listing of legends about the life of Guru Nanak. it also touches upon the sensitive topics of rising religious intolerance. For  instance, in one of the passages, Haroon talks about the rising fundamentalism in the education system. “The entire school curriculum of Pakistan Studies, which is a compulsory subject till university, has been designed in such a way to instill in the minds of the young students the separateness of Hindus and Muslims, and hence, justify the creation of Pakistan. There is no denying the fact that patriotism plays an important role in the education system of any country; but in Pakistan, nationalism is premised on hatred towards Hindus, which makes it dangerous.”

instance, in one of the passages, Haroon talks about the rising fundamentalism in the education system. “The entire school curriculum of Pakistan Studies, which is a compulsory subject till university, has been designed in such a way to instill in the minds of the young students the separateness of Hindus and Muslims, and hence, justify the creation of Pakistan. There is no denying the fact that patriotism plays an important role in the education system of any country; but in Pakistan, nationalism is premised on hatred towards Hindus, which makes it dangerous.”

In fact, I believe Haroon is also incredibly brave, when he expresses his heart at seeing the dilapidated Rori Saheb Gurudwara which is but a km or two from the Indian border. “Had Nanak rested a few kilometres further ahead, today his shrine would have been a thriving place. Devotees in colorful turbans and women with their hair covered in dupattas would java been sitting there right now, reciting the Granth. In the langar hall several more would have been eating. There would have been an entire market town around this shrine, selling religious paraphernalia. Various guesthouses and hotels would have been offering cheap accommodation to pilgrims coming from regions far away. This world existed only in my imagination. The truth was that Nanak, unaware of the historical consequences of his action, rested on what eventually became the wrong side of the border, and today this shrine is in shambles.”

Once more towards the end of the book, he yet again lapses into wishful thinking, saying; “Had Radcliffe made a minor error on the map of Punjab in front of him by only a few centimetres, the shrine of Kartarpur Sahib would have ended up in India and today hundreds of devotees would have been taking a dip in the holy water. The Ravi would have been a holy river, like it was at the time of the Vedas.”

In fact, the sheer honesty with which both Iqbal and Haroon deal with the issue of deliberate neglect and coercive mutation of religious places related to the Hindus and Sikhs in current dy Pakistan is very admirable. Through the pages, Haroon constantly talks about the right of religious fundamentalism and dogmatic fanaticism that is on the rise. These thoughts will surely find resonance for Indian readers, especially in light of all the cow-shed movements out here.

In the end, the book is a good easy read with a few snaps clicked by Iqbal. While, indeed the narrative could of course be tightened and language made racy, but nonetheless, this is a book that is encourages the reader to finish up fast. Haroon Khalid deserves all the kudos for putting together this book. Now all I can wish for as a reader is that if only we could give a visa to Haroon to Iqbal and have them roam across India and rest following the footsteps of Nanak for a second book, how nice it would really be. While we can wish for that book, we can surely read the current one and get informed.

the narrative could of course be tightened and language made racy, but nonetheless, this is a book that is encourages the reader to finish up fast. Haroon Khalid deserves all the kudos for putting together this book. Now all I can wish for as a reader is that if only we could give a visa to Haroon to Iqbal and have them roam across India and rest following the footsteps of Nanak for a second book, how nice it would really be. While we can wish for that book, we can surely read the current one and get informed.

-

Title: Walking with Nanak

-

Author: Haroon Khalid

-

Published: Westland Books

-

Price: 699

-

Review: 3/5