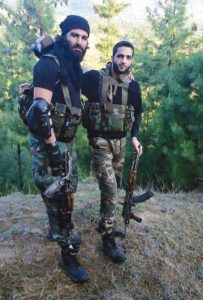

Kashmir is ablaze yet again. This time, over the killing of a terrorist Sabzar Bhat from the Hizbul Mujahedeen by the Indian security forces. The Valley seems to have erupted in support of the slain mercenary. Protests broke out in southern Kashmir, especially in Tahab area of Pulwama, Anantnag, and Shopian. The turmoil that has been kicked up on Bhat’s death seems to be like deja vu, a replay, of the anarchy that had gripped the Valley last year when Burhan Wani, another Hizbul terrorist, was gunned down by Indian forces.

Bhat’s death seems to be like deja vu, a replay, of the anarchy that had gripped the Valley last year when Burhan Wani, another Hizbul terrorist, was gunned down by Indian forces.

Bhat’s death seems to be like deja vu, a replay, of the anarchy that had gripped the Valley last year when Burhan Wani, another Hizbul terrorist, was gunned down by Indian forces.

Bhat’s death seems to be like deja vu, a replay, of the anarchy that had gripped the Valley last year when Burhan Wani, another Hizbul terrorist, was gunned down by Indian forces. So why is the northern-most region of India erupting in violence over the death of dreaded terrorists like Wani and Bhat? Why is that the populace in Kashmir more sympathetic to the cause of the radicals rather than those of nationals? Why is Kashmir burning? Why are the Kashmiris so thankless and so darn unpatriotic?

These are some of the basic queries that seem to crop up in the mind of the Indians across the mainland. Fuelled by jingoistic coverage of events on media, which almost borders on absurd, there seems to be an invisible wall that lies between Kashmir and India. We seem to be looking at each other through a coloured prism, unable to understand or comprehend.

What could be the reason for this disconnect? Do we really understand the problems that beleaguer Kashmir? Are we even aware?

A political issue or something more

The turmoil in Kashmir is often portrayed as an old issue, dating back to right when India attained independence from the British. The story of Kashmir and its accession to India is too well-known to require a repetition. But let me add that the wounds that were opened in ’47, have not healed or have not been allowed to heal by various elements within and beyond the borders.

Meanwhile, back in mainland India, Kashmir is portrayed as a law and order problem, Pakistan is blamed for fanning the flames of violence, and so on. The common argument is that till 1989, weren’t the Kashmiris cohabiting with Indians happily, letting the Yash Chopras of the world shoot Bollywood movies in the charming locales. Now, if azaadi was not desirable till the 90s, how did the game change so drastically and dramatically? Why did the Shikara-driving or Kahwa-sipping Kashmiri suddenly develop political ambitions and such massive ones?

Meanwhile, back in mainland India, Kashmir is portrayed as a law and order problem, Pakistan is blamed for fanning the flames of violence, and so on. The common argument is that till 1989, weren’t the Kashmiris cohabiting with Indians happily, letting the Yash Chopras of the world shoot Bollywood movies in the charming locales. Now, if azaadi was not desirable till the 90s, how did the game change so drastically and dramatically? Why did the Shikara-driving or Kahwa-sipping Kashmiri suddenly develop political ambitions and such massive ones?In our allergy to the word azaadi, what we really fail to realise is that it quite widespread in the Valley. From the rich owner of the houseboat to the lowly Gujjar horseman, everyone would at some time or the other talk about the concept of azaadi in varying degree of rapture. Instead of retreating into our patriotic shell, we need to face up to the call for azaadi, asking aloud as to whom is this freedom sought from; the Indian state or the state of affairs in Kashmir?

Solving it with might

In the stirring poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Samuel Coleridge tells a tale of a ship caught in a storm in the Antarctic waters and is rescued by the appearance of an albatross that guides the ship to safety. One of the mariners on board shoots the bird and brings bad luck to the ship. As the ship gets stuck in the ocean, the crew blames the mariner for the ill-luck and hang the dead albatross around his neck, as a sort of punishment or reminder of his crime.

Metaphorically, Kashmir seems like an albatross around India’s neck. The difference is, it isn’t yet dead but gasping for air, mortally wounded. Like the mariner in the poem who killed the beautiful bird with a gun, we too seem to be doing so, with lot many guns and an amazing array of them (AK47s, pellets, rubber, tear-gas).

Kashmir is being strangulated by the very hands that are meant to save it. And no prizes for guessing; it is the Indian military.

The first striking thing that you notice the moment you step out of Sheikh-ul-Alam Airport in Srinagar is the sheer numbers of security forces on the street. All over the roads, the crossroads, the corners, the hillocks, the distance, the near, the shops, the roundabouts, the camps, the schools, the ATMs, everywhere that you see are men in fatigues armed with automatics. One gets a rather odd feeling at seeing such pervasive military presence. I mean, you kind of wonder, whether you have accidentally landed in Kabul or Baghdad instead of Srinagar.

the camps, the schools, the ATMs, everywhere that you see are men in fatigues armed with automatics. One gets a rather odd feeling at seeing such pervasive military presence. I mean, you kind of wonder, whether you have accidentally landed in Kabul or Baghdad instead of Srinagar.

the camps, the schools, the ATMs, everywhere that you see are men in fatigues armed with automatics. One gets a rather odd feeling at seeing such pervasive military presence. I mean, you kind of wonder, whether you have accidentally landed in Kabul or Baghdad instead of Srinagar.

the camps, the schools, the ATMs, everywhere that you see are men in fatigues armed with automatics. One gets a rather odd feeling at seeing such pervasive military presence. I mean, you kind of wonder, whether you have accidentally landed in Kabul or Baghdad instead of Srinagar.Apparently, there’s a record in the Guinness Book as well that talks about Kashmir being the most militarised place on the planet. Figures vary from a few lakh to a couple of millions depending on bias behind the number. Nevertheless, even on a per capita Kashmiri basis, the sheer number of Indian military force is mind numbing.

So, what is the reason for this huge scale? Counterinsurgency, militancy, we are told. But then, there are hardly any attacks in Srinagar. Most of the attacks have been on paramilitary camps or on convoys. Of course, there are those stone-pelting in those university areas in Srinagar and other places, but that isn’t really an army job, after all even if there is an element of violence in it. That should be a law and order thing, a policing job. Why the hell do we have our paramilitary forces battling it out with our students? And this is my bone with the things in Kashmir.

For all my respect and admiration for the Indian army, I firmly believe that there is a clear-cut role that it performs. The army is meant to fight wars, kill enemy, attack, bomb, shatter, etc. Basically, the military is like a huge (read very huge) wrecking ball that you unleash on your opponents and whack the daylights out of them. In stray cases or exceptional times, the army can be banked to provide relief like say in the case of an earthquake or a flood, but largely army does just one thing, shoot, destroy and win.

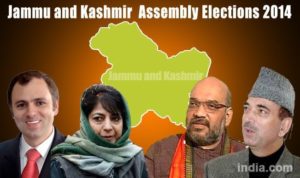

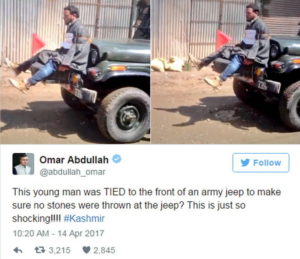

Maintaining law and order is the job of the police or the local administration. The army is just completely misfitted for such kind of thing. I mean it is like sending a wrestler to play golf, the bugger might get lucky with a few wild swings but would utterly fail when it comes to those delicate strokes nearing the hole. For instance, a policing force could never have the temerity to tie up a protester to a jeep and parade him openly. Yet, our forces are being coerced to do just that. They are being used say like say a watchman to look over buildings, ATMs or traffic signals, except they are a watchman with an AK47.

The trouble with this arrangement is the responsibility. The army usually does not function under the baggage of law, legislation, authorities, etc. Even the hallowed Geneva convention is something that is paid attention to, post conflict. For them every solution is just a function of force, big problem equals bigger force, smaller one can do with limited ops.

Ideally, the military should either be at the borders (LOC in case of Kashmir) or in the barracks. You should not have them policing the streets for a long time.

And that is where Indian state seems to have failed miserably. The trouble in Kashmir has been brewing since the 90s, and yet we have not been able to create a viable alternative for maintaining the law and order. The army with its roughshod mannerism of functioning has alienated the populace to such an extent, that a well-traveled Kashmiri businessman told me that even if the army was withdrawn from the Valley, it will at least take 100 years for all the wounds to heal. Every Kashmiri I met had an untoward incident to relate, it could be a direct brush with a patrol or a disappearance of a neighbor or a relative. Even if we were to filter it with the sieve of bias or for hyperbole, the numbers are still huge. How can you expect a population to live under a shadow of a gun, to continue on with life as if nothing is wrong? If you can’t, why should we expect the Kashmiris?

That also brings us to the essential question, as to why is there no viable ground force for policing the streets of Srinagar or Anantnag? Where are the cops?

The circle of vice

On the road to Sonmarg from Kashmir, we were constantly stopped by cops, this time in smarty blue uniforms. The driver constantly referred to them as “zokke” something, which going by the reluctance of the driver to translate must an ‘unparliamentary’ term surely. Anyways, the reason why the driver was muttering that term was because every time the ‘men in blue’ would stop him, he had to pay them off with a 50 or 100, even though every paper is in order. “That’s the way things are here,” confided Zahid the driver.

It is then that you truly realise the sheer scale of corruption that exists in Kashmir, it is  rampant, pervasive and in-your-face. Everywhere you look around, state officials or central ones are fleecing money. The politicians that live in lavish bungalows and move around in huge convoys seem to be the heart of this corrupt system. There’s just so much corruption in Kashmir that it has ceased to be of an issue at all for people to talk and discuss. It has gained as much acceptability as say a scoundrel of a Mama (mom’s brother) in the family.

rampant, pervasive and in-your-face. Everywhere you look around, state officials or central ones are fleecing money. The politicians that live in lavish bungalows and move around in huge convoys seem to be the heart of this corrupt system. There’s just so much corruption in Kashmir that it has ceased to be of an issue at all for people to talk and discuss. It has gained as much acceptability as say a scoundrel of a Mama (mom’s brother) in the family.

rampant, pervasive and in-your-face. Everywhere you look around, state officials or central ones are fleecing money. The politicians that live in lavish bungalows and move around in huge convoys seem to be the heart of this corrupt system. There’s just so much corruption in Kashmir that it has ceased to be of an issue at all for people to talk and discuss. It has gained as much acceptability as say a scoundrel of a Mama (mom’s brother) in the family.

rampant, pervasive and in-your-face. Everywhere you look around, state officials or central ones are fleecing money. The politicians that live in lavish bungalows and move around in huge convoys seem to be the heart of this corrupt system. There’s just so much corruption in Kashmir that it has ceased to be of an issue at all for people to talk and discuss. It has gained as much acceptability as say a scoundrel of a Mama (mom’s brother) in the family.Take any year’s annual budgetary allocation and you will see that Kashmir gets the lion share of it. In fact, Jammu & Kashmir has received 10% of all Central grants given to states over the 2000-2016 period, despite having only 1% of the country’s population. Yet, the roads in the state are as worse off than any other, there are no hospital chains or universities that the government is splurging the funds on. I mean, moving across the state, you tend to wonder where is the hell is all my money (as a taxpayer) really going. Then, just like it did to Archimedes, it dawns upon you, that all this money must be vanishing in all those accounts in Panama or Liechtenstein. That’s why a burning Kashmir is not such an unfavourable scenario to a handful of people. Imagine, you are powerful satrap — a politician or a bureaucrat, that is making huge amounts of money (unimaginable sums eh!) with no accountability since the whole state is in a turmoil, would you not wish things to remain the same. Status quo is good if your bank balance grows geometrically.

So, if the public sector is all corrupt and slimy what about the private sector? How is it doing in Kashmir?

Article 370: Boon or bane?

Having visited Himachal, Darjeeling, Munnar, your respect for Kashmir for one thing, the fact that it is not yet defiled by the vice of commercialisation. Most of the tourist places in India have been over the period of time been degraded into a money-making cash-cows. Scores of hotels, vehicles, restaurants, shops, etc., all crowd out any place in India, where a tourist would like to visit. Be it Munnar or Manali, be it Khajuraho or Dalhousie, unchecked commercialisation has its grip on all such places.

But Kashmir is different. Thanks largely to Article 370 that bars any non-Kashmiri from owning properties in the state, nature still exists like it largely did in most of the places (except the places of Srinagar and Gulmarg). It is not that there is no commercialisation in Kashmir, the scale has been significantly less. Thus, even in places like Gulmarg, you would find vast open spaces for children park, or a “mini Switzerland” in Pahalgam that has not yet been usurped in land grab. Because of this differentiation in legislation, private industry is virtually non-existent in Kashmir. And while that seems like a great idyllic thing for a tourist, it is not really so for the residents.

And even though the Kashmiri carpets and Pashmina shawls are a rage across the world, there’s hardly any private sector. Kashmiris are primarily dependent on two sectors, agriculture and tourism (am not counting the government related jobs or work). Any disruption in these two can be calamitous for thousands of families whose livelihoods are directly connected to these sectors. Natural calamities like floods in 2014, earthquakes, etc. affected badly those dependent on agriculture. Or like a drastic drop in tourism this year has afflicted many more.

Also, because of this special status, there’s hardly any economic integration of the region. While there are a few Cafe Coffee Day, there are no Dominos or McDonalds that one can see in Srinagar (McD is in Jammu, but that is different). Flipkart and Amazon don’t deliver in Kashmir even with card payments. Javed, the hotel manager of Forest Hill Reserve in Pahalgam had to get his phone delivered to his sister living in Pune who would then courier it to his home. There are also no theatres in Kashmir, so there’s no Bollywood etc. even though scores of movies are shot here. And if that is not enough, the internet in Kashmir (no Facebook or Whatsapp, only for tourist with roaming phones) reminds you of the 90s, when you had to say a special prayer to the lords above to able to surf the WWW with VSNL.

see in Srinagar (McD is in Jammu, but that is different). Flipkart and Amazon don’t deliver in Kashmir even with card payments. Javed, the hotel manager of Forest Hill Reserve in Pahalgam had to get his phone delivered to his sister living in Pune who would then courier it to his home. There are also no theatres in Kashmir, so there’s no Bollywood etc. even though scores of movies are shot here. And if that is not enough, the internet in Kashmir (no Facebook or Whatsapp, only for tourist with roaming phones) reminds you of the 90s, when you had to say a special prayer to the lords above to able to surf the WWW with VSNL.

see in Srinagar (McD is in Jammu, but that is different). Flipkart and Amazon don’t deliver in Kashmir even with card payments. Javed, the hotel manager of Forest Hill Reserve in Pahalgam had to get his phone delivered to his sister living in Pune who would then courier it to his home. There are also no theatres in Kashmir, so there’s no Bollywood etc. even though scores of movies are shot here. And if that is not enough, the internet in Kashmir (no Facebook or Whatsapp, only for tourist with roaming phones) reminds you of the 90s, when you had to say a special prayer to the lords above to able to surf the WWW with VSNL.

see in Srinagar (McD is in Jammu, but that is different). Flipkart and Amazon don’t deliver in Kashmir even with card payments. Javed, the hotel manager of Forest Hill Reserve in Pahalgam had to get his phone delivered to his sister living in Pune who would then courier it to his home. There are also no theatres in Kashmir, so there’s no Bollywood etc. even though scores of movies are shot here. And if that is not enough, the internet in Kashmir (no Facebook or Whatsapp, only for tourist with roaming phones) reminds you of the 90s, when you had to say a special prayer to the lords above to able to surf the WWW with VSNL.With limited prospects of prosperity, the Kashmiris are an unhappy lot. If you don’t see a good future for yourself or kids, will you not be disenchanted with the things that do exist? And, could it be possible that this disenchantment results in an inclination to pick up a stone and throw it at someone that you believe is responsible? In that manner, Article 370 that has saved Kashmir has also doomed it for good.

But is it the same everywhere in the state?

Jammu vs Kashmir

The moment you cross into the region of Jammu, you are confronted with a strange paradox. While the roads that cross Anantnag, Pahalgam, are quite like any other in India, pot-holed and rocky, Jammu is a different experience altogether. The roads are broad and even, there are tunnels that cut through hills, like the 9 km Chenani-Nashri Tunnel which is the longest in India or the 8 km Banihal Qazigund Road Tunnel that is going to come up. There’s a new swanky railway station in the holy town of Katra and so on. The economy seems to be booming in Jammu, the town of Katra is as commercial as say like Varanasi. There are even a couple of malls and multiplexes in Jammu. So, while the people in Srinagar have no option but to visit a couple of gardens on the weekends, the populace in Jammu is spoilt for options. Simply speaking, Jammu is like any other place in India.

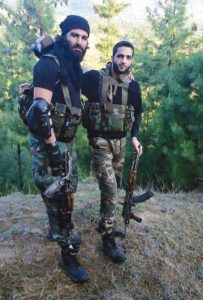

This stark differentiation in a matter of a 100 km seems to be building up consternation in the Valley. BJP is the primary political force in Jammu and being the central power, people in Valley talk about deliberate alienation. “Funds are all going to Jammu thanks to Modi and his men,” said one handicraft businessman in Kashmir. Over and over again, I heard people in Srinagar talking of how in a “holy-cowed” Hindu India, a Muslim Kashmir was  being punished and made to suffer. When it comes to Kashmir, not only is the infrastructure found lacking, but even the decision-making is under a cloud of suspicion. For instance, a complete collapse of tourism this year is being blamed on the government’s decision to hold elections in April, just before the start of the tourist season. “Everyone in Kashmir knows that any election in the Valley is always accompanied by violence. So, why would the government hold the election in April, knowing that the acts of violence in the Valley would scare off the tourists? They could have easily done it in the winters or after the season had passed. This was a deliberate kick on our backs,” confided a hotel-owner in Gulmarg.

being punished and made to suffer. When it comes to Kashmir, not only is the infrastructure found lacking, but even the decision-making is under a cloud of suspicion. For instance, a complete collapse of tourism this year is being blamed on the government’s decision to hold elections in April, just before the start of the tourist season. “Everyone in Kashmir knows that any election in the Valley is always accompanied by violence. So, why would the government hold the election in April, knowing that the acts of violence in the Valley would scare off the tourists? They could have easily done it in the winters or after the season had passed. This was a deliberate kick on our backs,” confided a hotel-owner in Gulmarg.

being punished and made to suffer. When it comes to Kashmir, not only is the infrastructure found lacking, but even the decision-making is under a cloud of suspicion. For instance, a complete collapse of tourism this year is being blamed on the government’s decision to hold elections in April, just before the start of the tourist season. “Everyone in Kashmir knows that any election in the Valley is always accompanied by violence. So, why would the government hold the election in April, knowing that the acts of violence in the Valley would scare off the tourists? They could have easily done it in the winters or after the season had passed. This was a deliberate kick on our backs,” confided a hotel-owner in Gulmarg.

being punished and made to suffer. When it comes to Kashmir, not only is the infrastructure found lacking, but even the decision-making is under a cloud of suspicion. For instance, a complete collapse of tourism this year is being blamed on the government’s decision to hold elections in April, just before the start of the tourist season. “Everyone in Kashmir knows that any election in the Valley is always accompanied by violence. So, why would the government hold the election in April, knowing that the acts of violence in the Valley would scare off the tourists? They could have easily done it in the winters or after the season had passed. This was a deliberate kick on our backs,” confided a hotel-owner in Gulmarg.A saffron-producing Kashmir seems to be increasingly at unease in a ‘saffronized’ India. The populace in Kashmir believes that they are being forsaken for their religious identity, while the ones in Jammu are being rewarded for theirs. There’s an undercurrent of this animosity and it is palpable, something that our dear politicians are not foolish enough not to exploit for their personal gains.

So, what are the respectable politicians up to in the Valley? Aren’t they trying to quell such misgivings that are making home in the minds and the heart of the populace?

The not-so popular poplars

It’s called Rusi Frass in Kashmir, but there is no Russian connection at all. The real name of the tree is Eastern Cottonwood or rather Populus deltoids. The plant had been introduced in Kashmir almost 40 years back as a part of Social Forestry Project to meet the needs of farmers and industries such as veneer and ply board, envisaged to alleviate pressure on forests. Besides meeting commercial needs, Poplar plantation was also intended at soil conservation, biodiversity enhancement and beautification of avenues and roads.

The results have been quite in contrast to what the intentions were. Walk down the streets of Srinagar, especially during spring, and all you will find is cottony wool floating in the air, or stacking up on the pavements. This cottony-rubbish is all pervasive in Srinagar

and creates a lot of issues. Health issues like asthma and allergies are on the rise, and people can be seen moving around with their hands covering their faces. The government seems to have woken up to the menace and is now spending crores cutting down the Poplar trees.

and creates a lot of issues. Health issues like asthma and allergies are on the rise, and people can be seen moving around with their hands covering their faces. The government seems to have woken up to the menace and is now spending crores cutting down the Poplar trees. In fact, the Poplar tree is a vivid example of how good intentions can go markedly wrong. Just like those politicians that are there in the valley. It was in 1987 that the Congress with National Conference rigged an election that would have changed history. The logic given was that the Muslim United Front or MUF was an umbrella front of separatist and would spearhead cessation from Indian state. Thus, the center and the state colluded and MUF was stalled from coming to power, with its leaders like Yasin Mallik (yes, the current one) jailed up. This was a watershed moment in Kashmir, because after this the populace lost trust in elections and politicians altogether. They were now a menace like the frass. For the man on the street, it scarcely matters who is there in the seat, Omar or Mehbooba, all are the same. And to me, this is the biggest tragedy of democracy.

From 1987 to today, there seems hardly any change in political machinations. The two political parties in the Valley, the NC and PDP are like the same side of a single-sided coin.  And whatever falls, it’s the populace that always loses. The parties pull each other down when in opposition, and go on to do the same very things when in power. For instance, the latest instance of uproar against the army, wherein an apparent protester had been tied up to a jeep and paraded, had been actually stoked by ex-CM Omar Abdullah, who shared the video on his Twitter feed for the first time. Even on Burhan Wani, the NC has been speaking in two tongues, referring to him as a terrorist and martyr. Meanwhile, Farooq Abdullah seems to have suddenly discovered the Kashmiriyat in him, talking about things like self-determination, dialogue with Pakistan and so on. PDP, the other party is no different. When out of power, it too is prone to incendiary pronouncements.

And whatever falls, it’s the populace that always loses. The parties pull each other down when in opposition, and go on to do the same very things when in power. For instance, the latest instance of uproar against the army, wherein an apparent protester had been tied up to a jeep and paraded, had been actually stoked by ex-CM Omar Abdullah, who shared the video on his Twitter feed for the first time. Even on Burhan Wani, the NC has been speaking in two tongues, referring to him as a terrorist and martyr. Meanwhile, Farooq Abdullah seems to have suddenly discovered the Kashmiriyat in him, talking about things like self-determination, dialogue with Pakistan and so on. PDP, the other party is no different. When out of power, it too is prone to incendiary pronouncements.

And whatever falls, it’s the populace that always loses. The parties pull each other down when in opposition, and go on to do the same very things when in power. For instance, the latest instance of uproar against the army, wherein an apparent protester had been tied up to a jeep and paraded, had been actually stoked by ex-CM Omar Abdullah, who shared the video on his Twitter feed for the first time. Even on Burhan Wani, the NC has been speaking in two tongues, referring to him as a terrorist and martyr. Meanwhile, Farooq Abdullah seems to have suddenly discovered the Kashmiriyat in him, talking about things like self-determination, dialogue with Pakistan and so on. PDP, the other party is no different. When out of power, it too is prone to incendiary pronouncements.

And whatever falls, it’s the populace that always loses. The parties pull each other down when in opposition, and go on to do the same very things when in power. For instance, the latest instance of uproar against the army, wherein an apparent protester had been tied up to a jeep and paraded, had been actually stoked by ex-CM Omar Abdullah, who shared the video on his Twitter feed for the first time. Even on Burhan Wani, the NC has been speaking in two tongues, referring to him as a terrorist and martyr. Meanwhile, Farooq Abdullah seems to have suddenly discovered the Kashmiriyat in him, talking about things like self-determination, dialogue with Pakistan and so on. PDP, the other party is no different. When out of power, it too is prone to incendiary pronouncements.The two parties have been playing this game for long, and Kashmir seems to have no reprieve. It kind of works to their benefit to collaborate this way, so that no other leader is given a chance be it Syed Shah Geelani, late Kuka Parey, Yasin Mallik or even Shabbir Shah. Just like they do to the Rusi Frass, all that the Kashmiris can do is cover their faces and continue on with life.

But, if things are really so bad in Kashmir, why isn’t there an uproar on the Indian heartland? Why are the people not rising up, holding candle marches on Janpath asking for peace and justice?

Of coloured glass

“Arre bhai, aap toh kashmiriyon ko studio mein gaali sunane ke liye hi bulate hain,” (you just call the Kashmiris in television studio so that you can abuse them) said one of the gent over an impromptu cup of Kahwa in Lal Chowk. The clock tower in the center of Lal Chowk is a pretty mundane one. It lies in a busy market area in downtown Srinagar. But over the years has gained much political prominence thanks to all the politics played around it. Hoisting the tri-colour on it, is an issue that can raise national heckles. But such tensions arise only on Republic Day and Independence Day, the rest of the time, no one bothers about it, while buying pherans or almonds. With the wife on a shopping spree in the area, I decided to give the Kashmiri Kahwa, one more shot. It had till now not aligned with my palate or my liking. Possibly amused by my weird facial expressions while drinking the concoction, an elderly gentleman started conversing with me. On knowing that I was a “media guy”, he went on to share his candid views on what he thought about the media guys. And believe me, he wasn’t the only one who shared similar views. Recently, Kashmir IAS officer Shah Faesal blasted Indian national media for spewing venom against Kashmiris, warning that it would cause a backlash.

The common grouse among Kashmiri is the manner in which the mainstream media  portrays them, especially a bespectacled hyper-patriotic anchor who goes ranting on Pakistan thinking that it will give them a migraine. The talk is about the mirch-masala, namely how issues in the valley are overtly exaggerated. For instance, right through my days in Kashmir, I could never spot an iota of unrest or crisis on the streets. Freely moving in Srinagar, Pahalgam, Gulmarg, Anantnag, and elsewhere, there were no ISIS flags that I spotted, no Pakistani ones either and yes, except one place on the road to Patnitop, most of the walls did not sport Wani graffiti. Yet, my folks in Mumbai, especially my mom, was worried about the safety because of all the continuing coverage on the news channels. She was seeing stone-pelters with masks disrupting life in Kashmir, while I was having shikara salesmen disrupting my reverie on Dal lake by pelting me with coloured flowers — hoping to make a quick sale. There seemed to be a big disconnect between what we thought is taking place in Kashmir, and what actually is. And sadly to say, the media seems to be widening the rift. Not closing it.

portrays them, especially a bespectacled hyper-patriotic anchor who goes ranting on Pakistan thinking that it will give them a migraine. The talk is about the mirch-masala, namely how issues in the valley are overtly exaggerated. For instance, right through my days in Kashmir, I could never spot an iota of unrest or crisis on the streets. Freely moving in Srinagar, Pahalgam, Gulmarg, Anantnag, and elsewhere, there were no ISIS flags that I spotted, no Pakistani ones either and yes, except one place on the road to Patnitop, most of the walls did not sport Wani graffiti. Yet, my folks in Mumbai, especially my mom, was worried about the safety because of all the continuing coverage on the news channels. She was seeing stone-pelters with masks disrupting life in Kashmir, while I was having shikara salesmen disrupting my reverie on Dal lake by pelting me with coloured flowers — hoping to make a quick sale. There seemed to be a big disconnect between what we thought is taking place in Kashmir, and what actually is. And sadly to say, the media seems to be widening the rift. Not closing it.

portrays them, especially a bespectacled hyper-patriotic anchor who goes ranting on Pakistan thinking that it will give them a migraine. The talk is about the mirch-masala, namely how issues in the valley are overtly exaggerated. For instance, right through my days in Kashmir, I could never spot an iota of unrest or crisis on the streets. Freely moving in Srinagar, Pahalgam, Gulmarg, Anantnag, and elsewhere, there were no ISIS flags that I spotted, no Pakistani ones either and yes, except one place on the road to Patnitop, most of the walls did not sport Wani graffiti. Yet, my folks in Mumbai, especially my mom, was worried about the safety because of all the continuing coverage on the news channels. She was seeing stone-pelters with masks disrupting life in Kashmir, while I was having shikara salesmen disrupting my reverie on Dal lake by pelting me with coloured flowers — hoping to make a quick sale. There seemed to be a big disconnect between what we thought is taking place in Kashmir, and what actually is. And sadly to say, the media seems to be widening the rift. Not closing it.

portrays them, especially a bespectacled hyper-patriotic anchor who goes ranting on Pakistan thinking that it will give them a migraine. The talk is about the mirch-masala, namely how issues in the valley are overtly exaggerated. For instance, right through my days in Kashmir, I could never spot an iota of unrest or crisis on the streets. Freely moving in Srinagar, Pahalgam, Gulmarg, Anantnag, and elsewhere, there were no ISIS flags that I spotted, no Pakistani ones either and yes, except one place on the road to Patnitop, most of the walls did not sport Wani graffiti. Yet, my folks in Mumbai, especially my mom, was worried about the safety because of all the continuing coverage on the news channels. She was seeing stone-pelters with masks disrupting life in Kashmir, while I was having shikara salesmen disrupting my reverie on Dal lake by pelting me with coloured flowers — hoping to make a quick sale. There seemed to be a big disconnect between what we thought is taking place in Kashmir, and what actually is. And sadly to say, the media seems to be widening the rift. Not closing it.The news channels on the mainland seem to be working in accordance with the Gadar-film Principle that is “Kashmir mango cheer denge” (rip you apart, if you ask for Kashmir). Almost every anchor will trip over themselves in emphasising the benign role of Indian government and that of the army. Any contrarian voices be it Prashant Bhushan, or Arundhati Roy will be vilified. I mean, they could indeed be wrong, but they do have a right to be heard. The result of such biased coverage is that for a bulk of Indians, Kashmiris are a thankless lot, like curs that feed on the bits thrown and biting the hand that feeds it.

And instead of marching on Janpath, the Indians will run away whenever there’s a  problem in the Valley. For instance, this year, tourism industry in Kashmir has crashed, with people keeping out due to fear of unrest. In spite of the fact that even at the peak of the unrest in the past few years, not a single tourist was ever harmed in an attack. The populace, knowing well its dependence on tourism, is extremely helpful and endearing. Yet, they suffer badly caught in the quagmire of unrest and misinformation.

problem in the Valley. For instance, this year, tourism industry in Kashmir has crashed, with people keeping out due to fear of unrest. In spite of the fact that even at the peak of the unrest in the past few years, not a single tourist was ever harmed in an attack. The populace, knowing well its dependence on tourism, is extremely helpful and endearing. Yet, they suffer badly caught in the quagmire of unrest and misinformation.

problem in the Valley. For instance, this year, tourism industry in Kashmir has crashed, with people keeping out due to fear of unrest. In spite of the fact that even at the peak of the unrest in the past few years, not a single tourist was ever harmed in an attack. The populace, knowing well its dependence on tourism, is extremely helpful and endearing. Yet, they suffer badly caught in the quagmire of unrest and misinformation.

problem in the Valley. For instance, this year, tourism industry in Kashmir has crashed, with people keeping out due to fear of unrest. In spite of the fact that even at the peak of the unrest in the past few years, not a single tourist was ever harmed in an attack. The populace, knowing well its dependence on tourism, is extremely helpful and endearing. Yet, they suffer badly caught in the quagmire of unrest and misinformation.So, if everything is so bad, sad, desolate, helpless, is there no silver lining? Is Kashmir destined to burn like this?

To be fair, if there can be peace and development in North East, there is no reason why it can’t be in Kashmir. What we need is a long-term plan and a will to bring about change. Thought needs to be given to justice, moving off the military, economic integration, and political expansion. Throwing money cannot be a solution, especially when the money seems to be deposited in benami accounts. The media too must play its role. If single incident of casteist murder creates such an uproar in our lives, why doesn’t the plight of all those pellet-stricken kids merit mainstream coverage?

Its high time now, average Indians need to be involved in the affairs. We need to land up in droves in the Valley and become ambassadors with our credit cards. Let’s converse with the Kashmiri, and grow over our jingoism, understanding their issues. Let not the word azaadi scare you, let’s stop making demons of Yasin Malik, Geelani, or even Umar Khalid. And finally, let’s stop deluding ourselves that an iron hand would be able to resolve the issue and stop blaming the external agents (who indeed are playing a role). If we have our home in order, no Pakistani or Talibani will ever be able to gain a foothold in the Valley. The government in the center and the one in the state needs to align and build towards that roadmap.

Khalid. And finally, let’s stop deluding ourselves that an iron hand would be able to resolve the issue and stop blaming the external agents (who indeed are playing a role). If we have our home in order, no Pakistani or Talibani will ever be able to gain a foothold in the Valley. The government in the center and the one in the state needs to align and build towards that roadmap.

Khalid. And finally, let’s stop deluding ourselves that an iron hand would be able to resolve the issue and stop blaming the external agents (who indeed are playing a role). If we have our home in order, no Pakistani or Talibani will ever be able to gain a foothold in the Valley. The government in the center and the one in the state needs to align and build towards that roadmap.

Khalid. And finally, let’s stop deluding ourselves that an iron hand would be able to resolve the issue and stop blaming the external agents (who indeed are playing a role). If we have our home in order, no Pakistani or Talibani will ever be able to gain a foothold in the Valley. The government in the center and the one in the state needs to align and build towards that roadmap. Back in 1992, a film by Mani Ratnam, Roja not only encapsulated our views on Kashmir but also shaped them. The scenes where we have the lead, Arvind Swamy arguing with the terrorist Pankaj Kapur, berating him for his misplaced ideology, these formulated our argument against terrorism. We now need to move to Haider from 2014, wherein some of the underlying conflict faced by Kashmiri has been captured. The shift from Roja to Haider has been a significant one, and we need to sally forth on that road.

We need to change and evolve our perspective. Take for instance, back in 2009, I had contemplated on the concept of Kashmir and Kashmiriyat, I still can’t claim to fully understand its relevance or role. But at least, I have made a beginning. I do hope a lot many more of my Indian brethren (and the ladies too) start doing so.

Jingoistic fervor might be good at times, but not worth when it disrupts the jannat (heaven) that we know as. A jannat that is haminasto, haminasto, haminasto…