Monthly Archives: June 2017

Walking with Nanak to uncover Sikh History

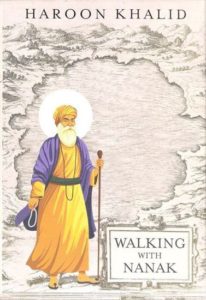

The first thing that immediately catches your attention is the beautifully illustrated cover, that has Guru Nanak in saffron robes, a staff in one hand and a rosary in other, all set for a long journey. And if the alluring illustration was not enough, the title itself invites you on a journey, Walking with Nanak, scores big in the first instance itself.

The author of this book is Haroon Khalid, who is a teacher by vocation and an avid traveler and writer by passion. This book is his third one, the other being A White Trail and In Search of Shiva. Basically, over the years Haroon has been writing on issues related to the minority communities in Pakistan, namely the Hindus and the Sikh. He is a sort of wandering chronicler who talks about the status and the current state of monuments related to Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan.

Search of Shiva. Basically, over the years Haroon has been writing on issues related to the minority communities in Pakistan, namely the Hindus and the Sikh. He is a sort of wandering chronicler who talks about the status and the current state of monuments related to Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan.

In the present book, Walking with Nanak, Haroon makes an interesting journey of all the important points of reference in Guru Nanak’s life as they exist in Pakistan. Guru Nanak was born in Rai Bhoi di Talwindi or what is known as Nankanasahib in 1469 and breathed his last in Kartarpur in 1539. In the 70 odd years that he lived on this planet, he made an astounding journey across the Indian subcontinent visiting places like Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia and so on. He apparently made 4-5 or five journeys that took him all over the place. Yet, at the end of it, he would return to his ancestral place in Pakistan at the culmination of each trip. Thus, because of this association with the first Sikh guru, the shrines in current day Pakistan are very important for the religion.

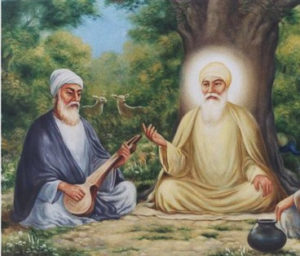

Guru Nanak traveled across all the places on foot and was accompanied by a companion  named Mardana, who was a Muslim man from his village. Mardana would accompany him and play rubab on which Guru Nanak would sing his poems. The bond between that of Guru Nanak and Mardana is that of a murshid (guide) and mureed (follower). Haroon too travels to all the sites accompanied by his murshid, Iqbal Qaiser, whom he considers to be his mentor (and much more). Being a scholar (self-taught) on Sikhism, conversations with Iqbal provide an interesting insight on what has been the religious state of affairs post partition.

named Mardana, who was a Muslim man from his village. Mardana would accompany him and play rubab on which Guru Nanak would sing his poems. The bond between that of Guru Nanak and Mardana is that of a murshid (guide) and mureed (follower). Haroon too travels to all the sites accompanied by his murshid, Iqbal Qaiser, whom he considers to be his mentor (and much more). Being a scholar (self-taught) on Sikhism, conversations with Iqbal provide an interesting insight on what has been the religious state of affairs post partition.

Relying on the Janamsakhis as a guide, Haroon “travels to historical places and witnessing the unfolding of history with imagination”. Through the pages we uncover the numerous legends pertaining to Guru Nanak’s life right from Sacha Sauda to Panja Sahib. We also encounter interesting legends like how Guru Nanak had cursed the village of Kanganpur with “May the village of Kanganpur prosper.” Meanwhile, he had blessed the village of Manakdele as,”this is a hospitable village and it was an honour to stay here. I hope that this village never prospers and remains small. May the villagers of Manakdeke scatter from this place to the different regions of the world.”

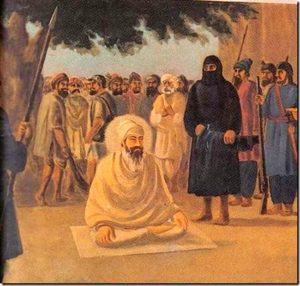

But Haroon does not limit himself to Nanak, he gives us an insightful overview of the Sikh history, giving us a ringside view of the intricacies of how the various Gurus rose to power.  And also tackling the contentious history of the relation between the Mughals and the Sikh Gurus. In a strange karmic way, the destiny of the Mughals seemed to be entwined with Sikh Gurus. For instance, the first Mughal king Babur had an encounter with Guru Nanak, whom he jailed for a few days in 1519. Post that in 1606, the 5th Guru Arjan Das was executed and Guru Hargobind was incarcerated on the orders of Emperor Jahangir. Then in 1675, the 9th Guru Tegbahadur was killed on the orders of Emperor Aurangzeb. And then in 1707, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb died, and the empire when into decline, the last living guru of the Sikhs, Guru Gobindsingh was murdered by Pathan horsemen in 1708. Haroon deals with this history at length, chronicling the transition of the Sikh Gurus as a religious head to that of a military one, like the formation of the Khalsa by Guru Tegh Bahadur. He also touches upon the fratricidal conflicts like the one with Prith Chand on the selection of his younger brother Arjan as the Guru. Or even the objection by Guru Nanak’s elder son and wife to the appointment of his disciple as a successor. Continue reading

And also tackling the contentious history of the relation between the Mughals and the Sikh Gurus. In a strange karmic way, the destiny of the Mughals seemed to be entwined with Sikh Gurus. For instance, the first Mughal king Babur had an encounter with Guru Nanak, whom he jailed for a few days in 1519. Post that in 1606, the 5th Guru Arjan Das was executed and Guru Hargobind was incarcerated on the orders of Emperor Jahangir. Then in 1675, the 9th Guru Tegbahadur was killed on the orders of Emperor Aurangzeb. And then in 1707, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb died, and the empire when into decline, the last living guru of the Sikhs, Guru Gobindsingh was murdered by Pathan horsemen in 1708. Haroon deals with this history at length, chronicling the transition of the Sikh Gurus as a religious head to that of a military one, like the formation of the Khalsa by Guru Tegh Bahadur. He also touches upon the fratricidal conflicts like the one with Prith Chand on the selection of his younger brother Arjan as the Guru. Or even the objection by Guru Nanak’s elder son and wife to the appointment of his disciple as a successor. Continue reading

Kashmir: An albatross around India’s neck?

Bhat’s death seems to be like deja vu, a replay, of the anarchy that had gripped the Valley last year when Burhan Wani, another Hizbul terrorist, was gunned down by Indian forces.

Bhat’s death seems to be like deja vu, a replay, of the anarchy that had gripped the Valley last year when Burhan Wani, another Hizbul terrorist, was gunned down by Indian forces.  Meanwhile, back in mainland India, Kashmir is portrayed as a law and order problem, Pakistan is blamed for fanning the flames of violence, and so on. The common argument is that till 1989, weren’t the Kashmiris cohabiting with Indians happily, letting the Yash Chopras of the world shoot Bollywood movies in the charming locales. Now, if azaadi was not desirable till the 90s, how did the game change so drastically and dramatically? Why did the Shikara-driving or Kahwa-sipping Kashmiri suddenly develop political ambitions and such massive ones?

Meanwhile, back in mainland India, Kashmir is portrayed as a law and order problem, Pakistan is blamed for fanning the flames of violence, and so on. The common argument is that till 1989, weren’t the Kashmiris cohabiting with Indians happily, letting the Yash Chopras of the world shoot Bollywood movies in the charming locales. Now, if azaadi was not desirable till the 90s, how did the game change so drastically and dramatically? Why did the Shikara-driving or Kahwa-sipping Kashmiri suddenly develop political ambitions and such massive ones? the camps, the schools, the ATMs, everywhere that you see are men in fatigues armed with automatics. One gets a rather odd feeling at seeing such pervasive military presence. I mean, you kind of wonder, whether you have accidentally landed in Kabul or Baghdad instead of Srinagar.

the camps, the schools, the ATMs, everywhere that you see are men in fatigues armed with automatics. One gets a rather odd feeling at seeing such pervasive military presence. I mean, you kind of wonder, whether you have accidentally landed in Kabul or Baghdad instead of Srinagar.