Fakir Chand Kohli was overwrought with uncertainties about the future. It was the early seventies and his employers, the Tatas, had asked him to take charge of their fledgling IT company, Tata Consultancy Services or TCS. Kohli had been associated with Tata Electric for over two decades and by his own admission was “a power engineer first”. Tatas were quite keen on Kohli taking charge at TCS due to his technical knack; after all he was instrumental in bringing mainframes in India around 1964 and completely computerising Tata Electric, one of the very few companies globally. Yet, he was not fully convinced.

Finally, his wife Swaran came to his aid and advised him to take up the challenge. Kohli took up the job on one condition that he could return to Tata Electric whenever he wanted to. And the rest as they say is history.

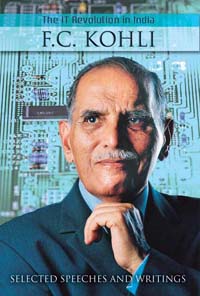

Often referred as the ‘father of Indian IT’ or the ‘Bheeshpithamha’ (grand sire), Kohli modestly  states that these labels do not affect him, though he adds, “I have received lot of respect from people. What more could I have asked for?”

states that these labels do not affect him, though he adds, “I have received lot of respect from people. What more could I have asked for?”

Early days

Born in Peshawar, British India; Kohli completed his graduation from Punjab University. His father ran a renowned department store in Peshawar. “It was one of the biggest in the country named as Kriparam Brothers”. Kohli was part of a large household and was the youngest kid, with 3 brothers and a couple of sisters.

Kohli is a voracious reader and he attributes this habit to his mother. “Though she had studied till standard 8th, she was an avid reader till her death in 1965. She used to read newspapers everyday, and regularly read fiction too. In fact, she maintained a small library that had religious as well as other books. I have inherited that trait from her,” he says.

He also doesn’t fail to add his indebtness to his elder brother, Devraj. “Due to family and personal reasons, he had to leave his education and join our family business. He never forgot that and desired his younger brother to have every opportunity that he could not. What I am today, I owe it all to him,” he says.

Kohli completed his B.A. in English (honors) and B.Sc in Applied Mathematics and Physics. But aren’t literature and applied mathematics at cross with each other? Kohli thunders, “Of course not. Isn’t a beautiful novel constructed on brilliant logic? Take the instance of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code…it talks about symbols and aren’t symbols the crux of mathematics?,” he questions.

After his graduation, Kohli applied for a scholarship and went abroad for further studies in 1945, first to Queen’s University, Canada and then his masters in Electrical Engineering from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Boston. He returned to India in 1951 for good.

By that time, his family had shifted to Lucknow and he was distraught to see them reduced to such desperate level. “We had to start life all over again. It was a big shock,” he reminisces. “It was a terrible thing (partition) to happen. I just could not fathom how it all happened. We were all so good to each other, so happy,” he adds.

Working with the Tatas

From ’51 onward, Kohli was at Tata Electric. He joined the company as chief load despatcher and went on to become the deputy general manager. He was intimately involved with the process of computerisation and digitisation of Tata Electric. “In 1964, we had acquired a mainframe and were looking at different ways to use computers. The first application to run was a project management software and we saved a lot of man-days and resources by using this utility and that clinched the case for computerisation,” he says.

Meanwhile, TCS was established in 1969 and subsequently he took charge of the company at the insistence of JRD Tata. His tenure at TCS is dotted with numerous episodes and incidents. Take for instance the story of how TCS had developed a permanent account number system for the Income Tax department and was nearly halfway through the process of computerising the department itself. Then the Janta Party came to power and the union finance minister Charan Singh derailed the whole process. “We missed a big opportunity in 1978-79. Imagine the gains that could have accrued with this kind of a mammoth project!,” he exclaims.

The other big miss according to Kohli was the kick out of IBM by the Janata government again. “I was never convinced about IBM moving out of India. As they had the technology, we needed them more. I am sure that if they had stayed on, the next plant for manufacturing mainframes would have been setup in India and not in Japan. We missed out on a whole generation of technology,” he rues. Though Kohli was instrumental in bringing IBM back in India, he was also responsible for setting up of the joint venture Tata-IBM.

The other big miss according to Kohli was the kick out of IBM by the Janata government again. “I was never convinced about IBM moving out of India. As they had the technology, we needed them more. I am sure that if they had stayed on, the next plant for manufacturing mainframes would have been setup in India and not in Japan. We missed out on a whole generation of technology,” he rues. Though Kohli was instrumental in bringing IBM back in India, he was also responsible for setting up of the joint venture Tata-IBM.

Of dreams and aspirations

Did he imagine that IT would be such a big thing in the years to come? “I was sure”, exclaims the emphatic Kohli. Way back then, Dr. Prem Gupta from ICR Computers had announced that India did not need more than six computers, but I believed otherwise and kept quiet. After all what are computers? They are just a tool that makes work easier. Now if you find a tool useful, do you go on and say that I will only use so many pieces in so many ways, or just go ahead and employ them in all means that are possible. You don’t limit you future, right?”

The future is going to be drastically different from today. “The best thing about technology is that it is undergoing constant change. Take for instance disk capacity in the eighties. Big machines used to have 3-4 gigabytes of storage capacity and now this PC on my desktop has close to 160 gigabyte,” he says.

According to Kohli, computing power in the future will be distributed through Internet though the Internet of the future will be quite different from the Internet of the present. “Currently 70 per cent of the traffic is what we term as spam. However, in the future we will be utilising the Internet far more efficiently,” he adds.

Retirement for dummies

Kohli continues to work on unabated. The octogenarian refuses to cut back on the work. “Retirement is for dummies,” he says. He is working with IITs and other institutions on different social projects that will touch the life of the common man. For instance, he is a great supporter of IT in agriculture, “We have not touched that sector at all,” he says. Also associated with a functional learning project, the pilot worked successfully and he has handed over the reigns to the local governments.

Kohli is an early riser, who on the days that he play golf wake up at 5.30 a.m. Otherwise, he wakes up at 6.45 a.m. to proceed for his morning walk. Kohli, who enjoys music says: “In my early days, it was film music like KL Sehgal, etc. During my stint in the U.S., I was exposed to Western classical music. When I returned back to India, I gradually began to take interest in Indian classical instrumental music. And right now, I am learning about Jazz,” he says. He admits about seeing films once in a while, “Right now we are watching a lot of Pakistani plays,” he adds.

He is currently grappling with the problem of hooking on his iPod to two PCs at the same time so that he can download music and files simultaneously. “There has to be a way and I will do it once I have the time,” he says. Kohli is also trying to convert his hundreds of VHS tapes into DVD, “I have a standalone 180 GB hardisk that burns DVD. I am in the process of converting my video tapes,” he says.

Kohli is also a happy family man. He has three sons, two settled in the U.S. and working on IT related industry, while the third is a doctor in India. His wife is a well-known consumer activist.

Kohli, the first recipient of the Dataquest Lifetime achievement award in 1991, quotes a line that he had said way back then, “to get recognised you need to live long, and if you live long, you will get recognised anyways.” But Kohli is not bounded by such limitations of time and providence. No matter, how much he lives, he will always be known as the IT messiah of India, the father, the grandfather, etc.