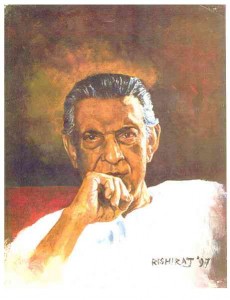

It must be a special day up in the heaven today, considering it is Manikda’s earthly birthday. In the lavish celestorium up above, there must be back-to-back screenings from the mast er’s repertoire, starting with Pather Panchali and if possible going on till Agantuk. Probably all his contemporaries and admirers like Renoir, Bergman, Bunuel, Fellini, Kurosawa must have arrived from their respective heavens, revisiting his masterpieces, discussing, dissecting and deliberating on them. Meanwhile, the birthday boy himself, would be sitting in a corner, away from the glare, dressed up in white dhoti-kurta and a shawl draped over his torso. Sitting cross-legged, a pipe hanging from his mouth sending out small small tufts of tobacco clouds quite like the steam engine in Pather Panchali that amused Apu and Durga. Satyajit Ray or Manikda as he was known within the film fraternity, must be observing all and sundry with intent full eyes, and probably thinking of what more embellishments could have been made to these movies or how many more he could have made, only if he had seen Bicycle Thieves a little earlier or the finances had flown in evenly through the years. Or just probably, he might be seeing those movies now not as a maker but as a viewer and enjoying them as thoroughly as we all do.

er’s repertoire, starting with Pather Panchali and if possible going on till Agantuk. Probably all his contemporaries and admirers like Renoir, Bergman, Bunuel, Fellini, Kurosawa must have arrived from their respective heavens, revisiting his masterpieces, discussing, dissecting and deliberating on them. Meanwhile, the birthday boy himself, would be sitting in a corner, away from the glare, dressed up in white dhoti-kurta and a shawl draped over his torso. Sitting cross-legged, a pipe hanging from his mouth sending out small small tufts of tobacco clouds quite like the steam engine in Pather Panchali that amused Apu and Durga. Satyajit Ray or Manikda as he was known within the film fraternity, must be observing all and sundry with intent full eyes, and probably thinking of what more embellishments could have been made to these movies or how many more he could have made, only if he had seen Bicycle Thieves a little earlier or the finances had flown in evenly through the years. Or just probably, he might be seeing those movies now not as a maker but as a viewer and enjoying them as thoroughly as we all do.

Manikda lived for 70 years on this planet and in it made some 28 feature length films and some half-a-dozen odd documentaries; he started at 32 and ended only when his time on tera-firma was up. In these 35-38 odd years, he completely reshaped the cinema in India and also across the globe. If ever one is coerced to take a single name whose influence on film making has been the most impactful, it has to be Ray. Though, he was not beyond the slur of numerous critics and self-appointed nationalists; yet he never did let anything or anyone bog him down and much like Gupi and Bagha in his two comic capers (which were heavily satirical as well) continued to enthrall his audiences across the globe.

“Not seeing Ray’s film is like living in the world, without the sun and the moon,” Kurosawa had stated once, and there is little more that can be added or appended to it. Manikda’s film encapsulated life and times of an India that was caught between the past, present and the future. On one hand, he captures the rigors and tribulations of rural life in Pather Panchali, Ashani Sanket. And then he brings the camera into the city, capturing the vagaries of modern life in Apur Sansar, Mahanagar, Jana Aranya, Agantuk, etc. And even when he dealt with all these serious issues, Manikda never preached and seldom took sides. His films were npt about good or bad or balck or white, they were merely grey much like the color they were shot in. It was as if, he was trying not to be biased for and against his characters, so in Jana Aranya, you have the son (the main protagonist) who is steadily becoming an instrument of crass capitalism, there is the idealist father who is trying to come to terms with the new realities of life and then there is indifferent brother and his caring wife. Between the four of them, Manikda captured and presented all the differing views that any Indian might be troubled or beset with.