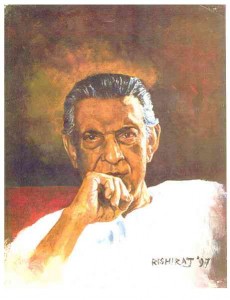

It must be a special day up in the heaven today, considering it is Manikda’s earthly birthday. In the lavish celestorium up above, there must be back-to-back screenings from the mast er’s repertoire, starting with Pather Panchali and if possible going on till Agantuk. Probably all his contemporaries and admirers like Renoir, Bergman, Bunuel, Fellini, Kurosawa must have arrived from their respective heavens, revisiting his masterpieces, discussing, dissecting and deliberating on them. Meanwhile, the birthday boy himself, would be sitting in a corner, away from the glare, dressed up in white dhoti-kurta and a shawl draped over his torso. Sitting cross-legged, a pipe hanging from his mouth sending out small small tufts of tobacco clouds quite like the steam engine in Pather Panchali that amused Apu and Durga. Satyajit Ray or Manikda as he was known within the film fraternity, must be observing all and sundry with intent full eyes, and probably thinking of what more embellishments could have been made to these movies or how many more he could have made, only if he had seen Bicycle Thieves a little earlier or the finances had flown in evenly through the years. Or just probably, he might be seeing those movies now not as a maker but as a viewer and enjoying them as thoroughly as we all do.

er’s repertoire, starting with Pather Panchali and if possible going on till Agantuk. Probably all his contemporaries and admirers like Renoir, Bergman, Bunuel, Fellini, Kurosawa must have arrived from their respective heavens, revisiting his masterpieces, discussing, dissecting and deliberating on them. Meanwhile, the birthday boy himself, would be sitting in a corner, away from the glare, dressed up in white dhoti-kurta and a shawl draped over his torso. Sitting cross-legged, a pipe hanging from his mouth sending out small small tufts of tobacco clouds quite like the steam engine in Pather Panchali that amused Apu and Durga. Satyajit Ray or Manikda as he was known within the film fraternity, must be observing all and sundry with intent full eyes, and probably thinking of what more embellishments could have been made to these movies or how many more he could have made, only if he had seen Bicycle Thieves a little earlier or the finances had flown in evenly through the years. Or just probably, he might be seeing those movies now not as a maker but as a viewer and enjoying them as thoroughly as we all do.

Manikda lived for 70 years on this planet and in it made some 28 feature length films and some half-a-dozen odd documentaries; he started at 32 and ended only when his time on tera-firma was up. In these 35-38 odd years, he completely reshaped the cinema in India and also across the globe. If ever one is coerced to take a single name whose influence on film making has been the most impactful, it has to be Ray. Though, he was not beyond the slur of numerous critics and self-appointed nationalists; yet he never did let anything or anyone bog him down and much like Gupi and Bagha in his two comic capers (which were heavily satirical as well) continued to enthrall his audiences across the globe.

“Not seeing Ray’s film is like living in the world, without the sun and the moon,” Kurosawa had stated once, and there is little more that can be added or appended to it. Manikda’s film encapsulated life and times of an India that was caught between the past, present and the future. On one hand, he captures the rigors and tribulations of rural life in Pather Panchali, Ashani Sanket. And then he brings the camera into the city, capturing the vagaries of modern life in Apur Sansar, Mahanagar, Jana Aranya, Agantuk, etc. And even when he dealt with all these serious issues, Manikda never preached and seldom took sides. His films were npt about good or bad or balck or white, they were merely grey much like the color they were shot in. It was as if, he was trying not to be biased for and against his characters, so in Jana Aranya, you have the son (the main protagonist) who is steadily becoming an instrument of crass capitalism, there is the idealist father who is trying to come to terms with the new realities of life and then there is indifferent brother and his caring wife. Between the four of them, Manikda captured and presented all the differing views that any Indian might be troubled or beset with.

Above all, Manikda was a brave film maker who sought to break conventions. This quint-essential (and now rather extinct) Bengali trait, stood him out in good stead. So, the female lead in his stories were not mere caricatures but real people, who could make decisions for themselves, in Pather it was the little girl Durga, the three different ladies in Devi, the lead protagonist in Ghaire-Baire and of course Charulata, the bravest of them all, who on being found to be romantically inclined to her brother-in-law, stands up with elan and is not a wee bit ashamed of her feelings (as the moral brigade would endorse for). Manikda’s biggest contribution to Indian cinema probably was his de-stereotyping the women in films; for the first time we saw women as they are in life, spunky, brave, confused, egoist, mysterious and zest-full.

Even though Manikda made films on issues and things that matter, he also knew how to have fun and make us do it as well. If any one doubts it even for a moment, just walk into a movie parlor and rent out Gupi Gyne Bagha Byne, the film about two village bumpkins expelled from their respective villages and subsequently meet ‘Bhooter raja’ and get 3 boons; musical talent, ability to travel anywhere and yummy food, all at a clap. The night scene, where Bhooter raja meets our friends and gives them a taste of ghostly song-dance is one of the best scenes even today. I still am unable to fathom how in 1968, he could make Bhooter Raja’s cheek light up like numerous light-bulbs, it gave the whole persona such a surreal effect.

Chiriyakhana was the detective-thriller that had Uttam Kumar playing the ace detective Byomkesh Bakshi. In Joy Baba Felunath, there was Soumitra Chatterjee (Manikda’s favorite) playing Feluda, a smart alec cigarette puffing detective from Calcutta with his aide Topshe, something of a Sherlock-Watson combine.

Hindi cinema was unfortunate in this aspect as Manikda made just two Hindi films, Sadgati and Shatranj Ke Khiladi. Both masterpieces in their respect, yet vastly different, Sadgati was a tale about a Brahmin priest killing a lowly untouchable and trying to hide his crime. While Shatranj Ke Khiladi dealt with the state of affairs in 1857, especially after the mutiny was quelled and how in its aftermath the Britishers vent about their business of lapping kingdom after kingdom, thanks to a divided and tardy Indians that lived then. Sadly, the audiences did not lap it up and Manikda decided to stick with Bengali cinema solely. The unique thing about Manikda’s films was that they borrowed heavily from literature, both in Bengali and then in Hindi, for instance Shatranj ke Khiladi was based on a story by Munshi Premchand.

Manikda took avid interest in all aspects of film making, right from scripting and dialogues, to designing costumes, musical composition, cinematography, etc. And yet, he was not a ‘jack of all’, but rather a ‘master of all’. It has been said that even when he was scripting the movie, he was shooting it and editing it on paper beforehand. In fact, his scripts are a collector’s edition now, because of all the jottings done in the side margins. And the music in his films be it the lilting Ravi Shankar tune in Pather Panchali, or the various songs in Gupe Gyne and Hirak Raja Deshe and the few in Charulata, are worth playing over and over again. He was very much musically inclined and that shows in all his movies.

Yet, movies were just one aspect of Manikda’s personality, even though it was the most important one. He was an amazing story teller and has composed many short stories and novellas for children in Bengali. He also created Feluda, the ace detective and there is the rather eccentric Professor Shonku who unravels strange mysteries and travels across the globe.

And then there is the famous urban legend of how in 1967, Manikda wrote a script for a film to be called The Alien based on his short story Bankubabur Bandhu. For some reason it could not be made. When Spielberg made ET in 1982, there was much similarity between the concept of Alien and ET. In fact, Manikda believed that Spielberg’s film would not have been possible without his script of The Alien being available throughout America in mimeographed copies.

Painting was another passion for Manikda and is known to have painted many covers for different novels, etc. Anyone who is yet not convinced of his greatness, I suggest you check out his profile on Wikipedia and numerous other websites. I can barely gloss over his films and personality even if I were to write reams and reams on him. I would suggest that his biography by Marie Seton and his own work, “Our films, their films” is a great starting point for any student of cinema or a follower of his films.

Cutting back here on planet Earth and today, I intend to celebrate Manikda’s birthday in much the same way that it is must be done in the heavens above. I will revisit the second part of the Apu Trilogy: Aparajito as it happens to be one of my most favorite films. Beside the story of Apu growing up, Aparajito has been shot in Benaras (or Varanasi), a city that holds a very special place in my heart and also happens to be my native place.

From the first sequence, where the train is shown crossing the metal bridge over the river Ganges, the film bristles with Benaras, there are the narrow lanes where cows block the path and spread their dung all around as if it is the most natural thing to do so. Then, there are those priests who make or rather try to eke a living by the sides of Ganges; the numerous stairs that one has to descend and ascend for daily bath especially at Ghats like Dashaswamedh and Assi. Also, there are the wrestlers who practice with heavy gadas at some of the ghats doing their exercises in the morning and late in the evenings. And the hundreds of temple that besot the city at every nook and cranny, Vishwanath Temple being the most important of all.

There is also another aspect of Benaras that is not much famous but is not missed by Manikda’s eye; the monkeys. During the time the Roy family stays in the city, the monkeys are very much a part of the story. There is a sequence where Apu on getting some money, goes and buys nuts and shares them with his monkey friends, who are shown to be enjoying themselves in a temple. And finally, their is the river Ganges that promises to take with it all the sins and indiscretions of whosoever taking mere 3 dips in the flowing water. Manikda came back to Benaras again in Joy Baba Felunath, but there it was meerly a city in the backdrop and not an important character as in Aparajito. Hence, there is some sort of personal attachment with the film.

In the meantime, Manikda if perchance there is some Net connection up there in the heavens and you happen to be surfing online checking on whether people still remember you and your films. Let me tell you that so long there is cinema, as long there will be you. And yes, many many happy returns of the day on your 88th birthday. Even after these 18 odd years, we still miss you and remember you through your movies.

My first Ray-film was Chiriakhana, described as his worst by himself. Yet I was totally thrilled with it, and even now, after watching all his movies.

Ray has moved me much more by his short stories, each of which reflects his love to mankind.

I am missing him