The quest for past

The quest for truth has been innate in the human mind, since time immemorial. Right from the Vedic times, as the Nasadiya sukta tell us, man has been wondering as to whom and how did the universe appear as they do now. While the quest has been undertaken on meta-physical levels, with questions being raised on the  practicality or impracticality of a supreme creator, this has in no way heeded the efforts to find the origins of the past. To know, from where it all began in a logical and chronological sequence. This quest for answers for roots lies at the very heart of archaeology.

practicality or impracticality of a supreme creator, this has in no way heeded the efforts to find the origins of the past. To know, from where it all began in a logical and chronological sequence. This quest for answers for roots lies at the very heart of archaeology.

In practical terms, archaeology is the physical effort undertaken to unravel the past. A scientific approach that either substantiates or debunks propositions from the past. The precise definition, reads something like this:

The systematic study of past human life and culture by the recovery and examination of remaining material evidence, such as graves, buildings, tools, and pottery.

But this quest for past has not been a recent one, many centuries yore, too people have been looking for answers in mythology, literature and religious books to discover the roots. The earliest historians, who documented India, were the religious or rather Buddhist travellers who came down to India with the objective of finding the real source of Buddhist literature.

Foreign nationals from across the shores or Himalayas have been frequent visitors to Indian since time immemorial as traders, travellers, scholars, and finally as rulers. One of the biggest fascinations for these travellers has been the immense wealth of epigraphical, architectural and sculptural material that is found in this region.

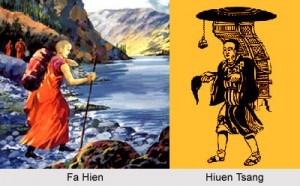

One of the first major documented visitors to Indian continent have been the  Chinese travellers Fa-hien (5th century CE) and Xuanzang (Hieun-Tsang-7th century CE) were interested in Buddhist remains and have left accounts of numerous cities and sites related with Buddhism, such as Nalanda, Bodh Gaya and Ajanta. Through their works, one is able to draw a clear anthropological picture of the time and lifestyles of Indians of those era.

Chinese travellers Fa-hien (5th century CE) and Xuanzang (Hieun-Tsang-7th century CE) were interested in Buddhist remains and have left accounts of numerous cities and sites related with Buddhism, such as Nalanda, Bodh Gaya and Ajanta. Through their works, one is able to draw a clear anthropological picture of the time and lifestyles of Indians of those era.

In fact the name that stands out or comes to the memory is that of Hsuen Tsang – Xuanzang [c.602 – 664] was a famous Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator who described the interaction between China and India in the early Tang period.

Born in Henan province of China in 602 or 603, from boyhood he took to reading sacred books, mainly the Chinese Classics and the writings of the ancient sages. While residing in the city of Luoyang, Xuanzang entered Buddhist monkhood at the age of thirteen and developed the desire to visit India. He knew about Faxian’s visit to India and, like him, was concerned about the incomplete and misinterpreted nature of the Buddhist scriptures that reached China. Continue reading